Elevating health care quality through centralization

The adoption of a clinical data enterprise

Executive summary

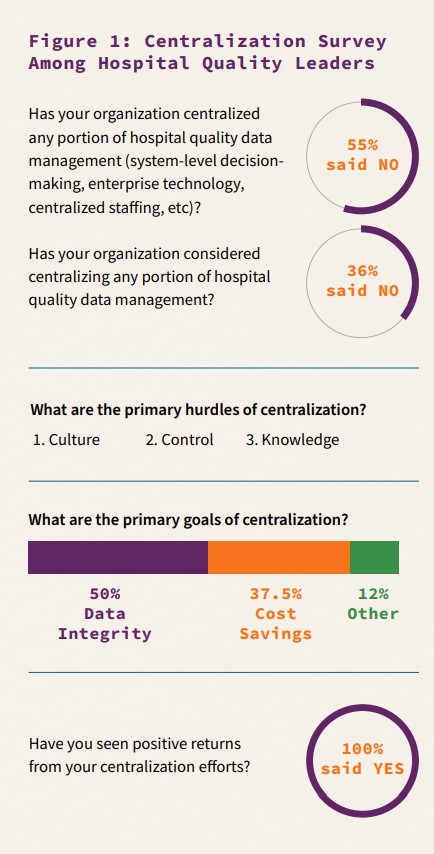

Health care providers have experienced favorable results from centralization strategies for at least a decade. Yet, quality departments have lagged their peer hospital departments. In this study, we interviewed Q-Centrix partner hospital system leaders who implemented at least one of three primary centralization strategies within hospital quality. The hospital systems included two of the top 10 systems in the country based on net patient revenue and member hospitals, three leading academic institutions, and two non-profit systems including one faith-based system that is among the top 10 non-profit systems in the country based on member hospitals and one regional system. Among the seven interviews, we sought to understand key drivers, hurdles, strategies and trends.

Following the qualitative portion of the study, we surveyed hospital decision-makers to validate the findings and understand perceptions of centralization within a larger population. This paper is the first piece in a series of research white papers and case studies on centralization in health care systems.

Findings

The specific elements that comprise centralization vary among hospitals, but the definition remains consistent: the process in which various practices and management of resources are streamlined in a facility or system to standardize best practice operations and drive positive outcomes.

- The most prominent trigger to centralize is growth in the number of facilities, the most common hurdle is the culture of a hospital. Notedly, physician engagement was not found to be a hurdle to centralization.

- Of hospital leaders that have implemented one or more centralization strategy, all have experienced positive results. Results of centralization are greater when implementing all three strategies at once: centralized decision-making, talent and technology. However, only 16% of leading organizations who have implemented a centralization strategy have engaged all three strategies at once.

- Leading health care organizations have experienced upwards of 20% cost-savings by incorporating centralization strategies. The cost-savings increased as work volumes rise and/or varied.

- Centralization efforts result in reduced administrative expenses and increased data integrity.

- Performance improvement resulting from improved data integrity was realized as early as three months after the centralization effort was completed.

Conclusions

Centralization is an effective strategy to address inefficiencies such as growing administrative costs and data integrity risks. These two inefficiencies are typically experienced as a result of growth. Few hospital quality departments are implementing a centralization program that incorporates decision-making, talent and technology. As a result of the reluctance to centralize, hospitals are forced to respond to rising data demands with increased investment and decrease the value of their enterprise clinical data.

Inorganic growth within health care systems

A study by the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) noted a 3.5 and 3.4 percent increase in the number of mergers and acquisitions in 2010 and 2011, respectively. The trend continued through the decade. Even in the first two quarters of 2020, during a global pandemic, Kaufman reported 29 mergers and acquisitions.

The inorganic growth trend within health care began largely as a result of the evolution to a value-based economy. In fact, “the transition from volume to value and the corresponding move to population health management required major capital investments and sophisticated management expertise of the sort that prompt[ed] even the most independent minded hospitals and health systems to consider their consolidation options,” stated Healthcare Financial Management Association in a 2016 report.

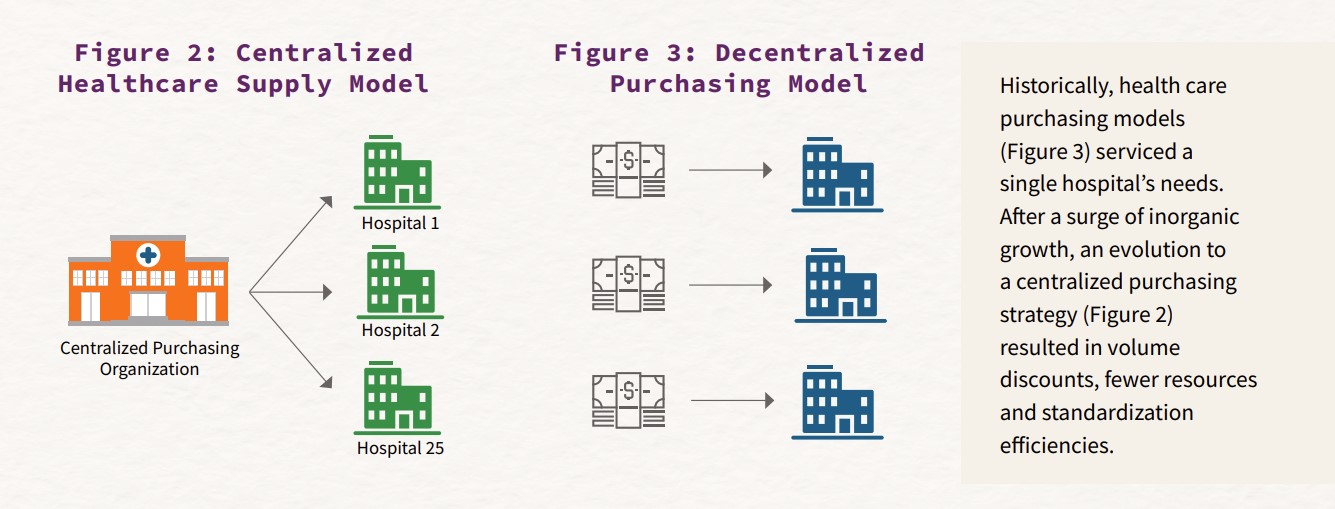

Centralized purchasing offers efficiency

As a result of the inorganic growth, centralized purchasing quickly emerged to maximize efficiencies and minimize redundancies across systems in areas like job roles. The supply chain structure centralized or outsourced control of logistics, shared services, electronic tools, and inventory and distribution. While centralization in health care is certainly not unique to supply chain, the early and positive returns from this function created a practical application for other areas of the hospital.

Obstacles to centralization: control and culture

Within health care organizations, there is a preference to retain local control, even at the cost of efficiency. Accordingly, a primary obstacle to centralization in hospital quality is the desire to retain control based on the perception of inequity created by centralization. To mitigate this concern, leading organizations develop and deploy a clinical data governance program prior to or in conjunction with their centralization strategy. A well-built clinical data governance framework identifies the talent, technology and investment for an enterprise approach to clinical data management that removes bias and improves performance.

Culture is foremost hurdle to centralization

Even more than the desire to retain control, the culture of an organization can determine the success of a centralization effort. Culture can manifest in

how an organization or individual justifies current behavior or rationalizes doing things differently. Culture-or the lack of a quality culture-is the foremost hurdle to centralized strategies in quality. Organizations that do not embody a quality culture often meet opposition to centralization due to the mistaken perception that an individual hospital or department’s clinical data exclusively benefits their teams. Hallmarks of a quality culture that would easily overcome these objections include executive sponsorship of quality, organizational quality imperatives, and system-wide quality responsibility.

Notedly, physician buy-in or engagement was not a significant obstacle to centralization. In fact, physicians were largely uninvolved in the decision to centralize; however, they played a prominent role in validating that the strategy produced accurate, actionable data.

Determinants and types of centralization strategies

The reasons for centralizing vary from hospital to hospital, but the most common determinant to centralization was inorganic growth driven by M&A activity. This type of growth is usually less predictable and makes investment planning more challenging. The result: redundancies and inefficiencies within the system. In the aftermath, centralization can offer cost savings by removing waste within the system.

Centralizing decision-making, talent and technology

The second most commonly cited factor that results in centralization is a change in leadership. New leaders identify opportunities for greater efficiencies upon their initial review of quality departments. What centralization strategy these new leaders engage, however, relates to their priorities and appetite for change.

There were three key strategies identified within this study: centralized decision-making, technology and talent.

- Centralized decision-making enables deliberate and aligned activities among quality departments.

- To reduce redundancies in job roles, hospitals followed the purchasing department example by centralizing staff.

- Finally, centralized technology and data management offered an enterprise view of performance and greater quality insights, physician engagement, and outcomes.

In each instance studied, engaging all three of the above strategies resulted in the greatest positive outcome.

Financial efficiency as a product of centralization

A top health care system has grown through acquisition since 1995 to include more than 75 hospitals concentrated throughout the South and Midwest. As a result, the system had amassed 85 full-time employees dedicated to clinical data management at an estimated annual investment of $10 million. Employees were distributed across the facilities.

The system recognized a 23% cost-savings by implementing one of three centralization strategies: staffing.

A top health care system comprised of more than 100 hospitals concentrated in the Southern U.S. had a history of large mergers and acquisitions as well as sustained organic growth through innovation. The system initiated a national centralization effort that engaged each of its regions. The return on investment fluctuated based on region; however, increased volume consistently resulted in higher returns.

The system recognized a 42% cost-savings by implementing two of three centralization strategies: staffing and decision-making.

A leading organization on the West Coast has become one of the nation’s 10 largest non-profit health care systems due to inorganic growth. In an effort to realize synergies, one region of the system engaged in a centralization effort of core measures and more than 10 clinical registries.

The region achieved a 61% cost savings by implementing all of the centralization strategies: decision making, staffing, and technology.

Rising administrative expenses drive centralization strategies

Administrative expenditures for U.S. hospital systems in 1999 were estimated to be 291 billion dollars, 25% of total expenditures for hospitals in the U.S. By 2019, it is estimated that these expenses had almost doubled. Health care leaders are challenged to find innovative financial solutions that positively impact patient care and outcomes but reduce administrative costs.

Administrative expense comprise the largest quality investment

Since 2017, quality leaders report their largest departmental investment is dedicated to staffing resources. In fact, experts estimate that up to 85% of the typical health care quality investment is dedicated to staff salaries, training and related costs, while the remaining investment is spent on technology and data management.

Savings grow as work increases

Organic or inorganic growth are common triggers to explore centralization as a strategy to reduce redundancies and inefficiencies within administrative expenses.

Examples of leading health care organizations who have undergone centralization strategies in quality (see Financial Efficiency as a Product of Centralization) illustrate that administrative cost-savings can be realized based on this effort. The exact financial return on centralization strategies vary based on the structure, size of system and characteristics of each organization. However, cost-savings increase as a result of removing redundancies and standardizing within the system. As a result, cost-savings increased in the research as volumes increased or work varied.

Centralization drives improved data integrity

Clinical data is used to inform patient care, satisfaction, and reimbursement. To be successful in these efforts, the integrity of the data is paramount. Data integrity is the accuracy, completeness, consistency and timeliness of data. In a survey of health care decision-makers, improved data integrity was the leading goal of a centralization strategies.

Misaligned priorities, incompatible technology, talent gaps, inefficient workflow, or weak quality assurance create risks to data integrity. Centralization strategies mitigate the risks to data integrity with a dominant decision-maker and standardization. Examples of leading health care organizations who have undergone centralization strategies in quality (see Data Integrity as a Product of Centralization and Sharp HealthCare) illustrate significant advances in accuracy, completeness, consistency and timeliness as a result.

Data integrity as a product of centralization

A top academic health system comprised of close to 20 hospitals within the Midwest documented data variation among their sites, most notably higher ICU mortality rates. A lack of data governance and disparate technology offered leadership opportunities to ensure greater data integrity.

The system identified and addressed errors in ICU admission protocols after a centralization effort that included two of the three centralization strategies: staffing and technology.

A top-ten U.S. hospital system concentrated throughout the South experienced more than a decade of inorganic and organic growth to amass almost 100 hospitals. The system leadership noted inconsistency in the regulatory data integrity from site to site.

The system experienced a 33% increase in CMS compliance in the first 3 months following a centralization effort that included all of the centralization strategies.

One of the largest faith-based health care systems in the country with almost 100 hospitals concentrated in the Midwest experienced data integrity issues that initiated a staffing and technology centralization effort within a six-site division.

The system reduced outliers by half within 6 months of a centralization effort. Within one year the data management was current and the hospitals were within the 99th percentile for the metric.

The science of centralization: best practice

There are several practices that can be adopted from leading organizations that have experienced higher returns on their centralization efforts.

Identify the total investment in health care quality

It can be difficult to understand the total health care quality investment within a health system; but it will become an important measure for success. Therefore, conducting an assessment to determine the total cost of ownership will be critical.

Develop a data governance program

Identify the needed expertise to develop data governance, identify staffing redundancies or select the appropriate enterprise-ready technology. If the expertise does not exist within the organization to develop the program, engage a third-party. Partnerships offer an objective perspective and experience that will only be additive to your efforts.

Nurture a quality culture

Quality cultures create an environment where all teams are focused on actions that result in better quality performance. Culture-building starts at the top where executive priorities should include quality outcomes.

Communicate change

Centralization strategies require excellent change management skills. As such, transparent, frequent communication to key stakeholders is integral. Communicate immediate- and long-term benefits and publish frequent updates on progress. Constant feedback and empowerment of those not in management can soothe a lost sense of agency.

Sharp HealthCare

Sharp HealthCare is one of California’s largest non-profit hospital systems including four acute-care and three specialty hospitals in San Diego, two affiliated medical groups and a health plan.

Driven by the opportunity to improve data integrity, Sharp HealthCare embarked on a centralization effort within quality. Sharp was driven to centralize due to documented data variations within the different system sites and a lack of visibility to system performance.

The system aligned decision-making, implemented clinical data governance efforts and engaged Q-Centrix as a partner to standardize workflow, team and quality assurance. As a result of the centralization efforts, the organization improved compliance for CMS by as much as 42% in 2 years.

Conclusion

Centralization was introduced as an efficient strategy for health care purchasing departments over a decade ago. The results of the efforts were unequivocally positive. Similarly, quality decision-makers who have centralized a portion of their work report that the results of their efforts are positive. Yet, centralization continues to be an underutilized strategy by health care quality departments throughout the country.